A Yankee Notebook

NUMBER 2111

January 3, 2022

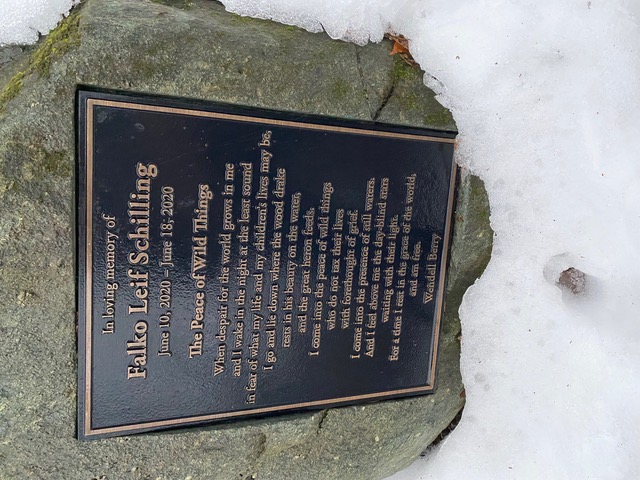

The Peace of Wild Things

EAST MONTPELIER, VT – A lightly worn trail runs up a north slope in Hubbard Park, where Kiki and I walk most days. Near the top, in a grove of magnificent red oaks, stands a beautifully built stone bench, just the right height, that invites a sit-down to think and breathe and watch the woods below. Beside the bench, set into a boulder, is a bronze plaque dedicated to the memory of an infant named Falko, who lived only eight days in midsummer of 2020. Beneath Falko’s name is Wendell Berry’s poem “The Peace of Wild Things.”

I don’t know how many times I’ve read it. It doesn’t scan like Frost or Tennyson; it doesn’t have a central metaphor. But embedded among its fellows, it does have a line that, in these almost unprecedented troubled times, resonates and revives in my head day or night: “I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief.”

It’s probably the ultimate irony of human existence that (to paraphrase Shakespeare lightly) when we once attain the upmost round, we then unto the ladder turn our backs, look in the clouds, and scorn the base degrees by which we did ascend. Here we sit, according to our own myth, at the pinnacle of creation or evolution. We’re blessed with the gifts of abstract thought, artistic expression, research and invention – the list goes on – and yet, in the words of another poet whose name escapes me, we’re still just rolling rocks down on each other.

The First Nations people of the Americas had it just about right. Only a dyed-in-the-wool Pollyanna would suggest they existed in a utopian world of peace and harmony. But, living as close to the earth, and depending directly upon it as they did, they revered it as their mother. The Cree of Canada, when offered many millions in exchange for the flooding of their ancestral lands by Hydro-Québec, responded (as if they had a choice) that the land is a resource forever, but money, spent, no longer exists. The land is gone now, and the reservoirs provide us “sustainable energy.”

Civilization has brought other gifts to the Arcadian wilderness. A missionary priest once described Heaven to the Inuit angakok Saltatha, who replied, “My father....You have told me that Heaven is very beautiful....Is it more beautiful than the country of the musk ox in summer, when sometimes the mist blows over the lakes, and sometimes the water is blue, and the loons cry very often?...if Heaven is still more beautiful...I shall be content to rest there till I am very old..” A meme currently making the rounds of the Internet features another elderly Inuk asking a priest whether, if he didn’t know about God and sin, he would go to hell. “No,” answers the priest, “not if you didn’t know.” The natural response from the old man: “Then why did you tell me?”

We highly evolved creatures carry our own hell with us. We regret what we’ve done, which mars our yesterdays; we fear, which clouds our tomorrows; and we worry, which steals our todays. We exult in reaching for the stars, yet carelessly poison the land, seas, and air that sustain us.

Meanwhile, the plants and animals we’re robbing of their livelihoods wait patiently (as if they, like the Cree, had a choice) for the masters of the universe finally to annihilate themselves, something which is within their reach, but somehow beyond their active imagining. Then, like the animals now returning happily to the toxic zones of Chernobyl, where you and I would perish, they will resume their lives as they were before atlatl-wielding biped nomads began to prey on the mastodons. We are the one species, given our heedless appetite for resources and space, that the natural world will miss the least when we are gone.

Vladimir Putin, his own vast country racked by poverty, virus, and repression, beats on the gates of his neighbor, Ukraine. President Xi, his nation on the road to world primacy over the backs of the less potent, fancies, perhaps, that he isn’t in his last years. Our own Congressional clown car, like a sackful of cats, scrambles for dominance, heedless of the vast power of the storm already breaking upon us from outraged nature. And I, like the First Nations, shake my head at the inescapable. Meanwhile up in the oak grove, Wendell Berry’s poem reminds us: Those who live simply, not taxing their lives with forethought of grief, will be here when we’re not even a memory.