A Yankee Notebook

NUMBER 2081

June 6, 2021

The Slow Death of a Killer

EAST MONTPELIER, VT – Our great-grandmother was our nanny when my sister and I were little, watching over us as we played on the sidewalk outside our building. She was a prodigious walker, as well. Every week she walked us over to the New York State Education Building to wander its wonderful museum – mastodon and whale skeletons, a stuffed elephant, a rose quartz cave, hundreds of birds’ eggs, and dioramas I could stare at for a long time – from a prehistoric swamp to scenes of Iroquois life.

She walked us every week up Lancaster Street, across Lark and Willett, to Washington Park. There were strange trees that we were told had been planted upside-down; old-fashioned multiple-person swings that an enterprising quartet of kids could really get going (though, looking back at the shifting parallelograms involved, threatened imminent amputation); a heroic statue of Moses amid beds of Dutch tulips, striking Mount Horeb for water for the wandering Israelites.

And the lake! Clearly artificial, but beautifully designed, with n Italianate boathouse and an arched bridge. A gravel walk around the perimeter was enlivened by dozens of tiny sunfish, emboldened by handouts, that hovered in as little as three inches of water. I was hooked.

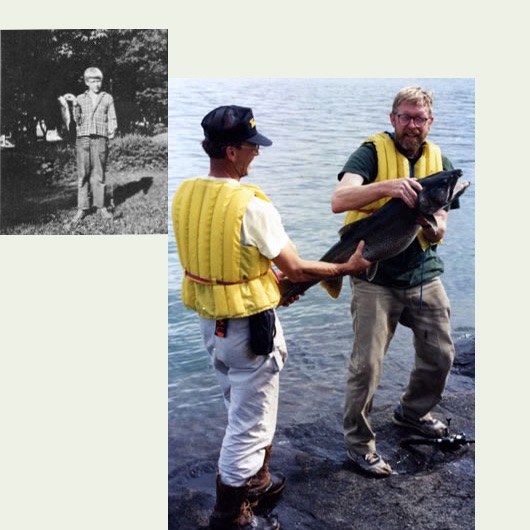

Looking back over eight decades, I can see that my early urge was to dominate, to own; and later, to kill. With a bent pin, wrapping twine, balls of white bread, and a jelly jar, I took home a few of my catch. I watched them fade, turn translucent, and die in the jelly jar.

Soon after – it was still during the war – we moved to Syracuse, where Onondaga Park and the many-acred Hiawatha Lake beckoned. It teemed with warm-water fish. I kept all but the smallest bluegills and perch, and my mother fried them up once I’d cleaned them. After a while I got sick of scraping dried fish scales off my arms, and began throwing the fish back. There was no virtue or philosophy involved; I just got sick of cleaning small fish. I did bring home one pretty good smallmouth bass, and in springtime, stringers full of white suckers. My mother refused to fry the suckers, so they were mixed into the compost pit that she used to mulch her Victory garden, and I used as a faithful source of fish worms. This worked well till a couple of the neighborhood dogs discovered the buried treasure. After that, we weren’t too popular with a couple of neighbors.

So it went: a gradual sophistication of methods and equipment and quarry, but none in any sense of the ethics of my sport. It takes little thought to thread a nightcrawler onto a fishhook, but it began to make me thoughtful when I skewered a live frog onto that hook, and he tried with all four feet to get rid of it. It would have taken a heart of stone to ignore that agony.

Luckily for me (as well as the bait), I shortly graduated to trout-fishing, and from worms to spinners and finally, flies. Fishing was becoming less a trip to the market than an art form. I still cleaned each trout as soon as I caught it, and stuffed fresh mint or watercress into the cavity. But another major evolutionary step was occurring: I found I didn’t care much to eat freshwater fish.

In the last twenty years or so, able at last to take canoe trips to the Canadian Arctic, I’ve caught and released lake trout, char, pike, and grayling beyond my youthful dreams. The thrill of the moment of hookup is as great as it ever was, the fight is just as exciting, and the joy of watching a great fish return to the rapids is the icing on the cake. I got into a big school of 30-inch female char one day – we could see each other – and as I released each one, she flipped me a faceful of ice water. I happily wiped my specs on my shirttail and went back to it.

I’m pretty sure that, like the narrator of A River Runs Through It, I’m done with fishing the big water. But that doesn’t mean it’s all over. Not yet. In another five weeks I’ll be drifting down the upper Missouri River with a dear old friend. The browns and rainbows out there are huge and voracious, as I hear they are in Heaven. But just to be on that river, imagining Lewis and Clark’s men toiling up the current over two hundred years ago, watching the Montana sky and the graceful pelicans, and spending long days outdoors with my buddy – I’ve got Heaven right here.