A Yankee Notebook

NUMBER 1944

October 22, 2018

A North Woods Getaway

It's when I'm weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig's having lashed across it open.

I'd like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it.

—Robert Frost

The late October darkness grows by discernible minutes a day; the outside cold creeps inexorably into the house; almost every avenue of information prattles or shrieks politics and disaster; I have no one but the puppy to help me out, and her only responses are snuggly or let's go for a walk in the woods!

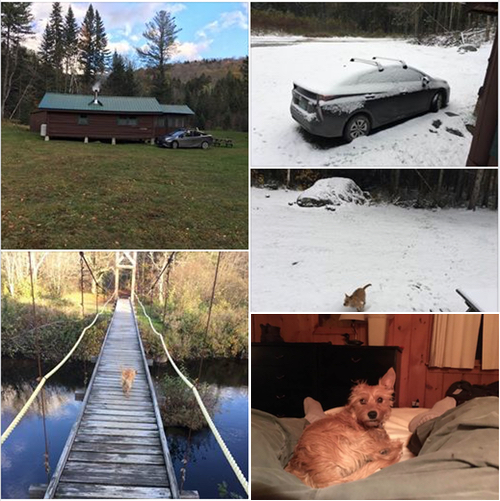

So we did. My initial thought was to drive to Gettysburg. But the thought of the long lines of roaring semi-trailers like performing elephants nose to tail on I-81; the melancholy of the battlefield, so reminiscent of our nation's current situation; having to walk Kiki on her leash wherever we went; and the thought that this year, instead of retracing Pickett's Charge from the Robert E. Lee statue to the stone wall where Hancock waited, and then, because for the first time there'd be no one waiting for me in the car at the Union lines, and I'd have also to do Pickett's retreat, (though I don't know what difference it would have made; Mother, God bless her, almost always got lost and wasn't there) – it was all too much. So I reserved a couple of cabins up north – one a do-it-yourself Shangri-La, and the other a three-meals-a-day sporting camp. No cell service, no wi-fi, no TV; just the ticking of a wood stove and the moan of the wind.

My desk calendar showed nothing doing between Wednesday and Saturday. Tuesday afternoon, on the advice of my tire guy, I had the lug nuts checked after about 75 miles on the snows. Mid-morning Wednesday it was off to the north, Kiki restless in her crate behind me. I announced to her, as we topped Orange Hill, that we were leaving the St. Lawrence watershed for the Connecticut. A stop in Lancaster for a Mac and cheese, and then, as we topped Milan Hill, another announcement: entering the Androscoggin watershed. Through the famous Thirteen-Mile Woods and a locked gate, and by two in the afternoon we were at the first cabin. It was colder inside than out, and the only kindling was rough splints of maple. But with a generous application of an old Valley News and lots of fanning, I got the stove going at last.

That evening, reading by headlamp, I saw a movement by the sink. Two mice were running along the top of the backsplash. Instantly, Kiki was everywhere, into what an old boss of mine in Texas used to call every crook and nanny. The little critters were everywhere. I recalled Longfellow's "I think of the Bishop of Bingen, in his Mouse Tower on the Rhine." She was at it most of the night, but I don't think she caught any. Between her hunting and my feeding the stove, I didn't catch many zeds, either.

It snowed three inches during the night. It was cemented firmly to the windows; but after a bit we got it melted, drove back down through the gate, and then west into Maine and Kennebago Lake. Another gate, nine miles of dirt road, and we arrived at Grant's, a sporting camp that got its start way back in 1875.

I'd been here before during fishing seasons. Fly fishing only, and really productive. This time I planned to do nothing but take walks on the camp trails, read my book, do crossword puzzles, and gaze out at the lake, which is a lovely example of preserved and protected wilderness. From my table by the window in the dining room I watched a loon fishing past the camp. When he dove, I started counting seconds, got to four minutes, and was interrupted by the cheerful waitress. I hope he survived.

The camp couture this time of year runs heavily to blaze orange; it's grouse season. There were hunters, mostly in pairs, from as far away as Mississippi, along with their cherished shotguns and bird dogs. They asked if I'd gotten any birds, and seemed nonplussed that my dog and I weren't there to hunt (though Kiki, who heard something down behind the Franklin stove in our cabin, clearly was). They ignored me after that, the way most people avoid slightly deranged old men.

I sat on one of the docks beside the lake with the afternoon sun warming my shoulders from behind. Kiki sniffed around the edges of the water and occasionally came back to sit beside me on the bench. It was all very peaceful, just as I'd hoped it would be. Like Robert Frost's boy bending his father's birches, I'd managed to get away from earth awhile, and the following morning would be set gently back down on it.